The West Memphis Three Case: An Evolving Story of Doubt & Misinformation

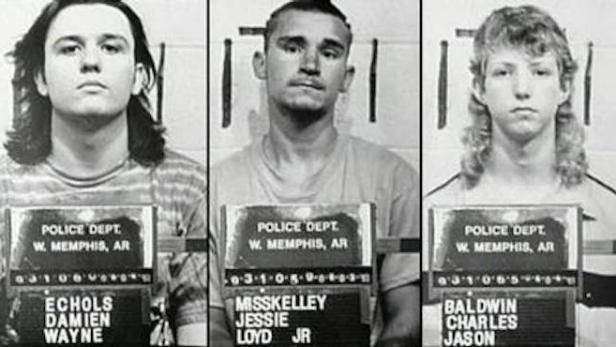

Damien Echols, Jessie Miskelley, Jason Baldwin [West Memphis Police Department]

Damien Echols, Jessie Misskelley, Jason Baldwin

WEST MEMPHIS, AR — Before Making a Murderer and before Serial, there was the West Memphis Three. The triple-murder case captured the nation’s attention after the release of the HBO documentary Paradise Lost: The Child Murders at Robin Hood Hills in June 1996. In August 2011, the three teenagers who had been convicted of the grisly killings, Damien Echols, Jason Baldwin, and Jessie Misskelley, Jr., were released from prison after being incarcerated in Arkansas for 18 long years. Echols had received a death sentence, and Baldwin and Misskelley were each given life sentences despite an arguably botched police investigation and questionable evidence.

Public outcry, activism by celebrities, and a total of three Paradise Lost documentaries played a major role in the trio’s exoneration. Today, the West Memphis Three are free after enduring nearly two decades of hell behind bars. But the case still lingers in the public consciousness, new developments continue to arise, and there are many questions that remain unanswered about the murders of three eight-year-old boys in West Memphis, Arkansas, on May 5, 1993. Who committed these unspeakable crimes if not the three who were legally convicted of them?

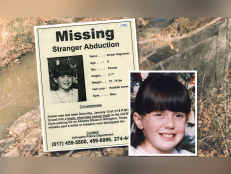

The facts surrounding the case are well known: Three eight-year-old boys — Steve Branch, Michael Moore, and Christopher Byers — went missing in West Memphis, Arkansas, on the evening of May 5, 1993. A frantic search of the boys’ neighborhoods and the nearby woods turned up nothing until the boys’ dead bodies were found in a creek bed the following afternoon.

Their naked bodies had been badly beaten, and appeared to be cut and mutilated. Suspicion quickly fell on three West Memphis teenagers seen as outliers in the community. Echols, Baldwin, and Misskelley were targeted because they dressed in black, had long hair, and listened to heavy metal music. In many places in the pre-internet age, especially in Arkansas, being “different” was sometimes akin to being a criminal, a “freak,” or a “weirdo.” Rumors of Satanism, ritual animal killings, and even human sacrifice spread like wildfire through the area. The police focused their investigation on Echols as ringleader and Baldwin and Misskelley as his loyal followers. While there was a report of a bloody man in a bathroom at a nearby restaurant bathroom on the night of the murders, and highly suspicious behaviors and activities of family members of the dead boys, the police believed they had their suspects, and they charged full-steam ahead and arrested Echols, Baldwin, and Misskelley for the killings.

All three teenagers were charged, tried, and sentenced for the murders of the three boys. The people of West Memphis breathed a sigh of relief and believed that their town was safer and that they could begin to heal their emotional wounds now that the case was solved.

But many outside of West Memphis believed that the trio had been unfairly targeted and were convicted on flimsy evidence and falsehoods. The first Paradise Lost documentary in 1996 brought the case to the attention of the general population, and two sequels, in 2000 and 2011, continued to explore the story and keep the plight of the West Memphis Three in the public eye. Celebrities such as Johnny Depp, Eddie Vedder, and Henry Rollins also joined the cause to raise awareness for Echols, Baldwin, and Misskelley as they languished behind bars. Finally, on August 19, 2011, all three men were released from prison after taking an Alford plea, which still leaves them legally responsible.

The documentary West of Memphis (produced by Damien Echols and Lord of the Rings director Peter Jackson) premiered in 2012 and focused on one other suspect in particular: Terry Hobbs, stepfather of Steve Branch, one of the murdered boys. But the story did not end there. Speculation, rumor, and missed opportunities continue to haunt the case.

Principal among these uncertainties is how the actual murders were actually committed. When the bodies of the boys were discovered, it was clear that Christopher Byers had suffered from genital mutilation. This detail caused investigators, and in turn the public, to believe that some kind of ritual abuse was performed on the boys, and that Byers had been singled out for some reason.

Abrasions inside the boys’ mouths and a particularly large wound on Steve Branch’s face highlighted the prosecution’s insistence that the victims were beaten savagely and tortured with knives by Echols, Baldwin, and Misskelley. Not until years later, after the three were locked away in prison, did it come to light that the wounds were not caused by human hands or weapons, but actually by wild animals in Robin Hood Hills. The boys were dumped into a creek in a wooded area and, until their bodies were found, they were preyed upon by wild animals, most notably, turtles. Renowned forensic pathologist Dr. Werner Spitz was hired by Echols’ lawyers to examine the evidence at the crime scene. In 2007, Dr. Spitz concluded that animal claw marks on the bodies were “obvious”and there was no way the injuries to Christopher Byers could have been caused by a knife. These facts alone, not to mention many other examples of misleading information, cast a long shadow of doubt on the state’s case against the West Memphis Three.

When the investigation is studied closely, it seems as if some officers, attorneys, and other influential people in West Memphis had their minds made up about who was responsible for the brutal murders almost as soon as the bodies were discovered. A county juvenile officer named Jerry Driver had a particular interest in Damien Echols and his outcast friends before the murders even occurred. Driver and juvenile probation officer Steve Jones were convinced that there was a dangerous Satanic cult at work in West Memphis, and that Echols and other members worshipped Satan and performed sacrificial rituals in the area.

Driver and Jones were so sure about their hunches that the two men would drive along country roads and through isolated areas during full moons to try to catch Satanic cults in the act. “We went everywhere in the world that summer, every time there was a witches’ Sabbath, we were out in force,” Driver told detectives.

There is no doubt that Damien Echols was a poor, troubled teenager from a broken home, but the scrutiny and paranoia surrounding him was pure Satanic Panic drummed up by Driver and Jones. The two juvenile officers contacted former police officer Dale Griffis, a self-proclaimed expert on the occult, a year before the 1993 murders to get his insight about Satanism and cult activity and how they might combat it in West Memphis.

When the bodies of the three boys were pulled from the murky drainage ditch on May 6, 1993, Steve Jones was on the scene and said, “Looks like Damien has finally killed someone.” Driver and Jones told anyone who would listen, including those in law enforcement, about their belief that Echols must have been responsible for the murders. Despite the fact that Echols had already been on his radar before the investigation, Dale Griffis was put on the stand during his trial and argued that the murders of the three young boys had “trappings of occultism,” and that evidence seized from Damien Echols’ home featured occult and Satanic drawings and writings.

Echols’ defense attorneys attempted to have Griffis discredited as an “expert,” but the judge allowed his testimony to proceed. There is no doubt that Dale Griffis’ damning testimony, and the relentless drumbeat of suspicion from Driver and Jones, played a role in Damien Echols’ conviction and sentencing.

Another puzzling element to the case is the testimony of one of the victims’ family members. Dana Moore, mother of Michael Moore, testified under oath during the trial that she saw her son Michael shortly after school ended at 3 P.M. on May 5, 1993. She went on to say that her son was in and out of the house with Steve Branch that day until she saw him for the last time riding bicycles around 6 P.M. with Branch and Byers. Dana Moore then testified that she sent her daughter, Dawn Moore, to go find her brother Michael and bring him home around dinner time. Dana Moore’s testimony has been accepted by law enforcement and the public for 25 years.

However, in early 2018, daughter Dawn Moore appeared on the Truth & Justice podcast and completely contradicted her mother’s testimony. Dawn told host Bob Ruff that her mother was not even home after school that day, and that Dana never sent her out around dinner time to look for her brother Michael. Dawn added that her mother didn’t even cook dinner that night, and instead the two of them went to dinner at a restaurant around 8 P.M. Dawn recalled that she last saw her brother and Steve Branch going into Robin Hood Hills sometime after school, possibly 4 or 5 P.M., well before her mother Dana even returned home.

If Dawn Moore is to be believed, then her mother blatantly lied to police and to a jury during the trial about her whereabouts that day and about seeing her son after school. Dawn went even further and told Bob Ruff that her mother was rarely home when she and her brother finished school, and usually came home later in the evening. Why would Dana Moore lie under oath about being home that day when her daughter says she clearly remembers she wasn’t? Was it to portray herself and her family in a better light? Dana Moore’s testimony is indeed odd if she in fact lied on the stand.

On the subject of police questioning, one glaring mistake sticks out like a sore thumb in the original investigation. Terry Hobbs, stepfather of victim Steve Branch, was not interviewed at the time of the original investigation in 1993. It is common knowledge that most, if not all, murder investigations begin with interviews with those closest to the victims. That’s why the decision by police to not question one of the victim’s stepfathers is so curious. In fact, it wasn’t until 14 years later, in June 2007, that Hobbs was finally interviewed by police about the triple murder.

As mentioned earlier, Terry Hobbs, like John Mark Byers before him, was fingered as a suspect in 2012’s West of Memphis after a hair found at the crime scene was genetically matched to him. Despite this evidence, no charges have ever been brought against Hobbs, who still firmly believes that Echols, Baldwin, and Misskelley are guilty of the murders. Ironically, former suspect John Mark Byers has publicly stated that he now believes Terry Hobbs is the killer (Byers is pictured below with Damien Echols).

There is no doubt that the Paradise Lost films swayed public opinion in a huge way. If not for the attention brought by the films, the case of the West Memphis Three would have been just another murder case in a place that most Americans never think about. But the first film in 1996 put one person squarely in the public’s, and ultimately investigators’, crosshairs. John Mark Byers, stepfather of victim Christopher Byers, became the unofficial “star” of Paradise Lost due to his bizarre behavior. Byers’ antics led him to be considered the prime suspect at one point, but he was ultimately exonerated by law enforcement. Byers later took issue with his portrayal in the films, and accused directors Joe Berlinger and Bruce Sinofsky of taking advantage of his vulnerable mental state during filming. Byers said he was usually drunk during filming, and added, “I wasn’t in my right mind. I tried to stay on medicine and marijuana, and they capitalized on that. They set me up to look like the fool.”

Another intriguing mystery surrounding the case comes from an eyewitness named Bryan Woody, who claimed he saw four, not three boys walking into Robin Hood Hills the day of the murders. Woody testified that he saw: “Two of them pushing bikes, one was carrying a skateboard, and one was just walking.” Woody’s testimony directly contradicts other eyewitness accounts that there were only three boys walking into the woods that day, and differs from the story Jesse Misskelley, Jr., told authorities when he was interrogated. Who was the mysterious fourth boy that may have been with Steve Branch, Michael Moore, and Christopher Byers that day?

In 2014, the case took another strange turn when the activist hacker group Anonymous weighed in and launched “Operation WM3” to seek justice for the three murdered boys. Anonymous argued that after reviewing the case files there was no doubt that Echols, Baldwin, and Misskelley were innocent. The hackers went further and accused the police of having strong evidence pointing to the people responsible, and of not pursuing the case further due to embarrassment caused by mistakes made in the past. The group called on then–Arkansas Governor Mike Beebe and the West Memphis Police Department to pardon the West Memphis Three and to launch a new, unbiased investigation into the 1993 murders to bring the killers to justice. The speaker on the video warned the killers, “The clock is ticking…You cannot escape justice.”

In the April 27, 2018, episode of the Truth & Justice podcast, host Bob Ruff teased listeners with a vague mention of the possibility of some new developments in the West Memphis Three case. He said that his team may have to end his coverage of the case sooner than expected, as there is the potential that they may have to back off due to legal reasons. No other clues about what that could mean have been forthcoming, and no information has turned up from other sources.

It has now been 25 years since the tragic murders of Steve Branch, Michael Moore, and Christopher Byers. No one else has been charged with the brutal killings since the West Memphis Three were released from prison in 2011, and Echols, Misskelley, and Baldwin are still legally the killers. As it stands, there seems to be as many unanswered questions today as that horrible day in May 1993 when the lives of so many in West Memphis were changed forever.

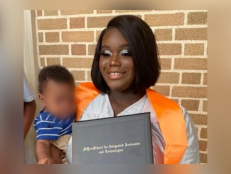

For more on this case, watch the “West Memphis Three” episode of Investigation Discovery’s True Crime With Aphrodite Jones on ID GO now!

Watch Now:

A Silver Screen Icon Vanishes In Open Water On A Cold November Night. What Happened To Natalie Wood?

Read more: The History Reader, MaraLeveritt.com, MaraLeveritt.com (2), Devil’s Knot: The True Story of the West Memphis Three, MemphisFlyer.com, KASU.org, JivePuppi.com, JivePuppi.com (2), ABC News, Truth & Justice, podcast episode 509, Truth & Justice podcast episode 512, StatementAnalysis.com, RitualAbuse.us, Famous-Trials.com, Untying the Knot: John Mark Byers and the West Memphis Three

![Relisha's photo is shown age-progressed to 14 years. She was last seen on March 19, 2014. [via National Center for Missing & Exploited Children]](http://investigationdiscovery.sndimg.com/content/dam/images/investigationdiscovery/crimefeed/legacy/2021/05/relisha-rudd-missing-ncmec-052121.png.rend.hgtvcom.231.174.suffix/1621619534494.png)