5 Burning Questions We Still Have About The Steven Avery Case

Despite being 10 hours long, Netflix’s true-crime docuseries “Making A Murderer” left viewers with plenty of unanswered questions about Wisconsin man, Steven Avery, who was convicted of murdering 25-year-old Teresa Halbach in 2005. While the series made a compelling case that Avery’s guilt was not so cut and dry, there are few things that still have us scratching our heads. While the Internet theorizes, we’re still left wanting answers.

Luckily, Investigation Discovery — which has covered the Avery case extensively — will be airing a special, “Steven Avery: Innocent or Guilty?” ,on January 30 at 9/8c, which promises to look at critical details surrounding the Steven Avery murder trial at the center of the Netflix project. As part of the special, ID will share exclusive interviews with Jerry Buting, Avery’s former defense attorney, and Ken Kratz, former Calumet County DA and prosecutor in the Avery and Dassey cases.

Here are some questions we’re still dying to know the answers to…

1. Was Steven Avery’s “sweat DNA” found in Teresa Halbach’s car?

Not exactly. The filmmakers behind “Making A Murderer” have received some flack for not including all of the State’s evidence against Avery in the series, including what Prosecutor Ken Kratz has referred to as “sweat DNA” under the hood latch of Halbach’s car. However, there is no such thing as sweat DNA. DNA is found in all nucleated cells, and while Avery’s DNA was found under the hood latch, there has never been a test to determine that a sample of DNA came specifically from perspiration. According to State v. Norman, “people often slough off skin cells containing DNA when they sweat … thus, DNA is often present on articles of clothing.”

When this evidence was presented at Avery’s trial, his attorneys argued that his DNA could have ended up under the hood latch due to contamination — a crime lab expert testified that he went under the hood after handling other evidence and did not change his gloves. Their alternative argument was that the DNA could have been planted.

SOURCE: Vulture

Investigation Discovery

Avery’s former attorney, Jerry Buting, maintains that local authorities targeted Avery from the start

2. Who deleted Teresa Halbach’s voicemails?

Unfortunately, it is impossible to say. What we do know is that Halbach’s family became concerned about her well-being after calling her phone and discovering her voicemail was full; as it was unlike her to leave her messages unchecked, and she hadn’t been heard from, they decided to go to the police. At trial, a network engineer from Cingular Wireless testified that the call log presented by the prosecution did not have enough messages to have “filled up the full capacity of the mailbox,” leading Avery’s lawyers to surmise that some of her messages had been deleted. But by whom?

Mike Halbach, Teresa’s brother, testified that he successfully guessed Teresa’s voicemail password and listened to her messages in hopes of finding some clue as to her whereabouts, but said he didn’t “believe [he] erased any messages.” Later, Teresa’s ex-boyfriend, Ryan Hillegas, testified that he guessed her Cingular account password, which allowed him to access and print her phone records off the Internet, but it’s unclear whether this would have allowed him access to her voicemails as well. Now, some theorists have suggested that Hillegas might have deleted his own voicemail messages from Halbach’s phone, concerned that their content would have led police to consider him a suspect, but there is no proof of that, though there is an argument to be made that by virtue of being her ex, he should have been considered a suspect anyway. Regardless, unless and until someone comes forward, whoever deleted Halbach’s messages will remain a mystery.

SOURCE: Bustle

3. What would it take to get Brendan Dassey a new trial?

Last year, after Wisconsin’s Supreme Court declined to consider Dassey’s appeal, his lawyers filed what’s called a “federal habeas petition,” arguing that his conviction should be vacated because he had been illegally arrested and imprisoned, and his rights had been violated by both the police and his court appointed attorney, Len Kachinsky. Now it’s up to U.S. Magistrate Judge William Duffin of Milwaukee to decide whether this is grounds for a new trial or even Dassey’s release — but the judge could just as easily reject the petition. Michael O’Hear, a professor of law at Marquette University, told PostCrescent.com that habeas corpus cases are extremely difficult to win.

“It’s a very high standard to get relief from a habeas,” he said. “The federal court will defer to decisions by state court unless they are unreasonable, or if they have egregiously misfired. … The [success] rate for federal habeas is very low. The statistics I’ve seen most recently showed maybe a 1 to 2 percent success rate nationwide.”

SOURCES: PostCrescent.com; People

Investigation Discovery

Why isn’t there any blood from Halbach inside Avery’s home?

4. Will there ever be a blood test that concretely proves whether the blood in Halbach’s car was planted?

Avery’s new attorney Katherine Zellner recently told The Wrap, “We are confident Mr. Avery’s conviction will be vacated when we present the new evidence and results of our work to the appropriate court,” leading many to wonder what this “new evidence” might be. HLN’s resident attorney Anahita Sedaghatfar believes it might have something to do with the vial of Avery’s blood that the defense alleged was tampered with and used to frame their client.

First, to review: the Manitowoc County Clerk’s Office had a vial of Avery’s blood on file ever since his first conviction for rape in 1985 (he was exonerated in 2002 after spending 18 years in prison). Fast forward to Avery’s trial for the murder of Teresa Halbach: In the process of building their framing defense, Avery’s attorneys learned about the vial of blood, and discovered that both the larger evidence container and the vial itself showed evidence of tampering, including a puncture mark in the cap that could have been caused by a needle. At trial, they alleged that Detective James Lenk knew about the blood vial and would have had motive and opportunity to plant Avery’s blood in Halbach’s car.

The prosecution, meanwhile, was allowed to ask their friends at the FBI to create a new scientific test that would refute this allegation. The test the FBI created was made to detect the presence of a chemical preservative called EDTA, which would only be present in blood that did NOT come from a free-flowing source like Avery himself. The FBI’s expert testified that he tested three swabs of blood from Halbach’s car, and did not detect EDTA, the implication being that the blood in the car could not have come from the vial. However, EDTA tests are considered unreliable — including by the FBI! The issue is that just because the test didn’t detect EDTA in the swabbed samples, doesn’tmean it’s not there, especially since it’s unknown what the test’s limit of detection was. The ONLY firm result that could be reached with a test like this based on the information available is if EDTA is detected, thus concluding that the blood couldn’t have come from a free-flowing source.

Avery’s attorneys have made it clear that one of the best avenues for having their client exonerated or at least granted a new trial lies in proving conclusively that the blood in Halbach’s car contained EDTA. Their hope has been that the renewed attention on Avery’s case would lead to scientific development of such a test, which is absolutely within the realm of possibility. Whether that test would spit out the result they hope for remains to be seen.

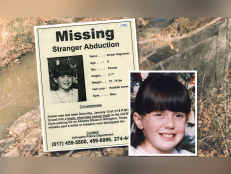

Former district attorney of Calumet County, Ken Kratz, asserts that Avery targeted Halbach/ Photo: Investigation Discovery

Investigation Discovery

Former district attorney of Calumet County, Ken Kratz, asserts that Avery targeted Halbach

5. Did Halbach complain about Avery to her boss before her death?

Not exactly. Prosecutor Ken Kratz has alleged that Halbach became concerned after an incident on Oct. 10, 2005, when Avery greeted her wearing only a towel, leading Halbach to tell her employer she did not want to return to Avery’s residence.

However, according to “Making A Murderer’s” filmmakers, “Teresa was the only ‘AutoTrader’ photographer who covered Manitowoc,” and had made at least 15 visits to the Avery property before her death.

As for her fear of Avery following the towel incident, Dean Strang, an attorney for the defense, explained that this assertion was “blown up” by a receptionist for ‘AutoTrader,’who testified that the subject came up during a short conversation about unusual or funny things that have happened on the job. “[Halbach’s] reaction when [Avery] came from his little splash pool in a towel was ‘ew,’ but not that she was unwilling to go back there,”Strang said. Ultimately, this evidence was excluded by the judge and never presented to the jury.

Want to learn more about the Steven Avery case? Investigation Discovery is partnering with NBC News’ Keith Morrison to re-examine the evidence. STEVEN AVERY: INNOCENT OR GUILTY premieres Saturday, January 30 at 9/8c. The Front Page special will provide insight into unanswered questions from the Netflix series MAKING A MURDERER.

Main Image: AP Photo/Morry Gash, Pool/ Steven Avery’s defense attorney, Jerry Buting, holds up Teresa Halbach’s keys that were found in Steven Avery’s trailer bedroom

![Hannah Graham [left] was found murdered on Sept 24, 2014; Morgan Dana Harrington [right] was found in January 2010. DNA has linked the two murders to Jesse Matthew Jr.](http://investigationdiscovery.sndimg.com/content/dam/images/investigationdiscovery/crimefeed/legacy/2022/09/charlottesville-police-department-hannah-graham-virginia-state-police-morgan-dana-harrington-09082022.png.rend.hgtvcom.231.174.suffix/1662659468172.png)