Crime History: Adolph Weber, “The Boy Murderer” Who Killed His Whole Family

FOLSOM, CA — On September 27, 1906, guards at Folsom State Prison escorted Adolph Weber into the facility’s gallows.

The time had come for Weber, 22, to pay the ultimate price for committing what The Los Angeles Times had deemed “one of the most revolting [atrocities] in the annals of criminal history” and became, in fact, the first mass murder on California’s court records.

Julius Weber and Mary Weber, Adolph’s parents, were German immigrants who had risen to wealth and promise in the city by way of a hugely popular and successful beer-brewing business in Auburn, California.

On the evening of November 10, 1904, nothing seemed amiss, as Julius and Mary ate dinner with their daughter Bertha, 18, and youngest child Earl, an eight-year-old who suffered from developmental disabilities.

Even the absence of Adolph at the table was common. He regularly disappeared for days at a time and, even when if he was home, he ate by himself. After an exemplary childhood, adolescence had apparently rendered the young man … troubled.

In his teens, Adolph took to dressing in black and carousing with prostitutes. Workers swore he tortured small animals in a shed on the family’s property. He openly raised fighting cocks and, if he sensed one lacked the proper combative attitude, he’d crush its head under his boot in front of the others to impart a “lesson.”

On top of that, a family doctor diagnosed Adolph as a “chronic masturbator.” At his own insistence, Adolph underwent a circumcision at age 16 hoping to “cure” the issue. It didn’t work.

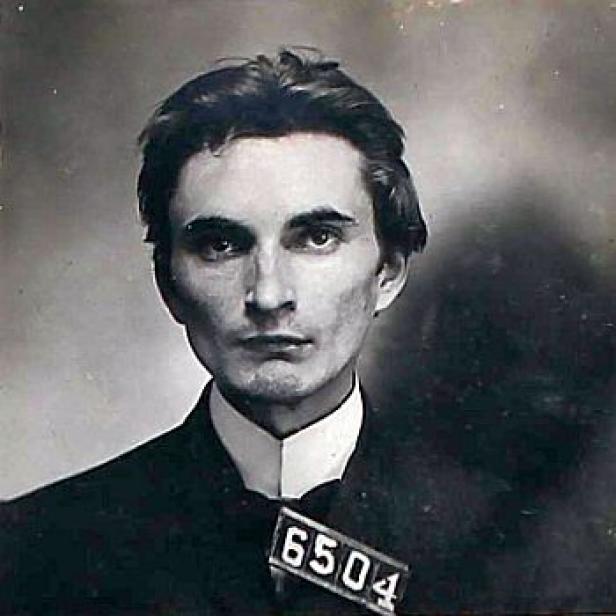

Adolph Weber [Folsom State Penitentiary]

Rumors even arose that Adolph had been the masked robber who held up the Auburn Union Bank the previous May and made off with $5,500 in gold. Those rumors turned out to be true.

All that darkness within Adolph boiled over into a cruel homicide on that November night. After dinner, Julius reportedly walked in on Adolph masturbating. His son responded by whipping out a .32-caliber pistol and pumping a bullet into his father’s chest.

From there, Adolph confronted the other Webers downstairs. He shot Bertha first. As his mother scrambled for the telephone, Adolph shot her once in the back and again in the head. He then caved in Earl’s skull with the butt of the gun.

Afterward, he dragged the bodies into a front room and lit the house ablaze. As he casually walked outside with smoke beginning to billow behind him, Adolph noticed blood spatters all over his pants.

Dashing to a nearby general store, Adolph frantically bought an ill-fitting pair of trousers. He ran back home, broke a window, and tossed his old, bloodstained pair into the rising flames.

Witnesses watched him do this and, at first, thought maybe it was just Weird Adolph being weird.

Following a medical exam of the obviously bullet-riddled and bludgeoned bodies, police arrested Adolph. Investigators also recovered his bloody garment. On top of that, they discovered 20 pieces of gold from the bank robbery hidden out in the barn.

Greed figured as the primary motive, as sole survivor Adolph stood to inherit the entire Weber brewing bounty — which he did, just in time to hire an A-list defense attorney.

Amid massive media coverage that drew both public outrage and female admirers who sent violets to the jailhouse, Adolph Weber became known as the “boy murderer.” He also hired the famous litigator Ben Tabor to defend him. The trial commenced in February 1905.

Tabor, a famous attorney who had become a living legend during California’s Old West period, put up a good fight, but after just three days, the jury returned a guilty verdict. The judge ordered Weber to be executed.

Several appeals delayed the execution slightly, and the governor momentarily mulled allowing Weber to be examined to see if he might be legally insane. Ultimately, though, the punishment stuck.

After walking up the 13 steps to the noose, the hangman asked if Weber had any last words. The condemned prisoner responded:

“I have no statement to make, no writing to leave behind, and I have no statement to make regarding the disposition of my body.”

Witnessing the execution, a Los Angeles Times reporter wrote:

“Never did an assassin meet death with firmer step, or cooler nerve, than did the boy murderer of Auburn.”

Following the Weber case, California officially enacted a “parricide law” to make it illegal for children to inherit money from their parents if the children have, in fact, murdered those parents.

Beyond that and the mass-murder aspect of the case, Sacramento-based historian Michael Meloy states that the Weber saga also holds a special place in California legal history, as it shows the state’s evolution from lynch mobs of the Old West to an official justice system. As Meloy puts it:

“It was about the struggles between the frontier and a more modern viewpoint. There were suggestions in the local paper that there were moments when the public nearly decided to take justice into their own hands.”

Either way, on this day in 1906, Adolph Weber joined his other family members in death.

Watch Now:

![Selena receives a Grammy Award at The 36th Annual Grammy Awards in March 1994 [via Getty Images]](http://investigationdiscovery.sndimg.com/content/dam/images/investigationdiscovery/crimefeed/legacy/2021/03/getty-selena-quintanilla-perez-1309300538.png.rend.hgtvcom.231.174.suffix/1617128091576.png)