How The Murder Of Vincent Chin Changed Detroit’s Asian American Community — And Michigan Law

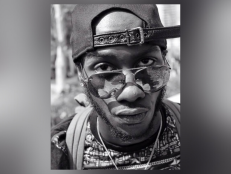

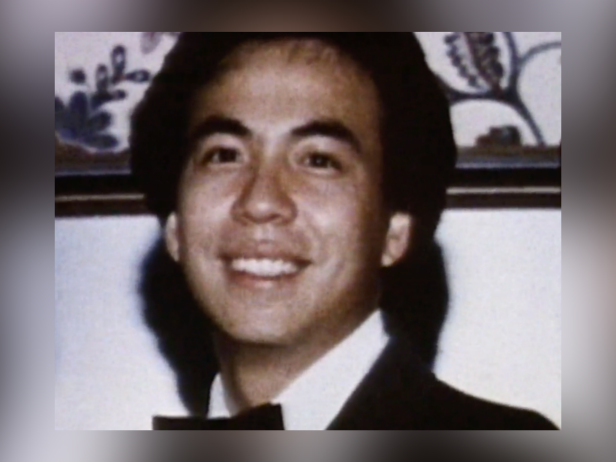

Vincent Chin was beaten to death while out celebrating his impending wedding and was buried a day after the ceremony should have taken place.

Warner Bros. Discovery, Inc. (Screenshot from ID's "Fatal Encounters")

The case of an Asian American man who was beaten to death in Detroit in the early 1980s paved the way for major changes in Michigan’s legal system — even if justice, many say, was never served.

On the evening of June 19, 1982, Vincent Chin, a 27-year-old draftsman of Chinese descent, was celebrating his impending wedding with a bachelor’s party at a Detroit strip club. At the establishment that night were Ronald Ebens, a Chrysler foreman, and his recently laid-off autoworker stepson, Michael Nitz.

At the time, the city was home to automakers Ford, Chrysler and General Motors, but the industry was in steep decline as a result of Japanese imports and increased competition from the country.

CNN reported that according to a dancer, Ebens yelled at Chin that night, “It’s because of you little motherf****** that we’re out of work.”

Chin then got into a physical altercation with Ebens and Nitz, who were both white, and the men were removed from the club. Once outside, the three continued fighting. At one point during the brawl, Nitz and Ebens chased Chin, and Ebens used a baseball bat to beat him in the head once they caught up to him, according to CNN.

Chin fell into a coma, and he died from his injuries four days later. He was reportedly buried the day after he was to be married.

Eben and Nitz were initially each facing a second-degree murder charge in the case. Later, however, Ebens was able to plead guilty and Nitz no contest to a reduced manslaughter charge.

On March 16, 1983, nearly nine months after Chin’s death, the father and stepson went to court for sentencing. The two defendants, their defense attorneys and the judge were the only people present at the hearing, author Paula Yoo wrote in her book about the case, From A Whisper to A Rallying Cry: The Killing of Vincent Chin and the Trial That Galvanized the Asian American Movement.

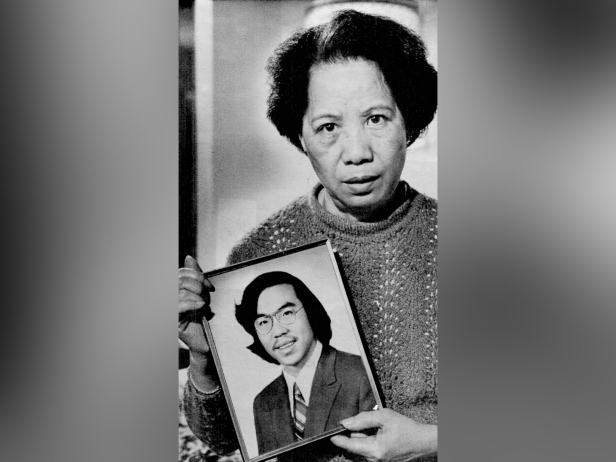

Associated Press

In this Nov. 2, 1983, photo, Lily Chin holds a photograph of her son Vincent, 27.

In those days, Wayne County prosecutors reportedly were overwhelmed with their caseloads and often didn’t show up for sentencing hearings. According to CNN, the victim’s mother, Lily Chin, as well as other family, friends and witnesses also failed to attend because they weren’t notified of the hearing since it was not common then for judges to listen to impact statements.

In the empty courtroom, the judge, Charles Kaufman, heard from only the defendants and their attorneys. They claimed Chin was the initial aggressor. Each defendant was sentenced to three years’ probation, assessed a $3,000 fine and ordered to pay court costs. The judge, according to AAWW, later wrote in a letter to a civil rights group: “These weren’t the kind of men you send to jail.”

The sentences sparked outrage, and a newly formed organization called American Citizens for Justice brought the case to the federal government. The government decided to pursue charges, and Ebens and Nitz were indicted on counts of conspiracy and interfering with Chin’s right to be in a place of public accommodation. The ensuing federal civil rights trial became the first that involved an Asian American in United States history.

In June 1984, Nitz was cleared of all charges against him. Ebens, who wielded the bat used in Chin’s death, was convicted and received a sentence of 25 years. He was released on bond after an appeal and a court later reversed the conviction, citing government legal errors and alleged witness coaching, according to CNN.

In 1987, following a second trial, Ebens was acquitted and later found not guilty.

In the end, neither Ebens nor Nitz spent a full day in jail in connection with Chin’s killing.

The case had multiple impacts on Michigan that continue to reverberate to this day. As a result of Chin’s death, manslaughter sentencing laws were changed in the state and now include minimum sentencing requirements. Families also give victim impact statements in court for judges to consider. Prosecutors must appear at all hearings.

Outside the court system, the slaying deeply affected the Asian American community — and continues to do so. A generation was forced to find ways to effect change through activism, political action and other means.

According to the Asian American Legal Defense and Education Fund, Ebens apologized for the role he played in Chin’s death. In a 2012 interview, he claimed killing Chen was “the only wrong thing I ever done in my life.”

“It’s absolutely true, I’m sorry it happened and if there’s any way to undo it, I’d do it,” said Ebens, then 72. “Nobody feels good about somebody’s life being taken, okay? You just never get over it…Anybody who hurts somebody else, if you’re a human being, you’re sorry, you know.”

“It changed my whole life,” Ebens said. “It’s something you never get rid of. When something like that happens, if you’re any kind of a person at all, you never get over it. Never.”

CNN reported that according to Helen Zia, an activist who served as the executor of Chin and his mother’s estate, the victim’s family did not accept Ebens’ apology.

“It was a complete failure of the criminal justice system,” Zia told the news channel of the case.

Still, she noted, “It wasn’t all for naught. A whole movement had been created, organizations formed … there were new generations of Asian Americans who were becoming civil rights lawyers because of this case.”

For more on this case, stream Fatal Encounters: “Killer Swing” on discovery+.

![Natalee Holloway [main photo] disappeared on her senior class trip to Aruba in May 2005. Now, Joran van der Sloot [inset] finally confessed to her murder.](http://investigationdiscovery.sndimg.com/content/dam/images/investigationdiscovery/crimefeed/legacy/2023/10/fbi-natalee-holloway-102423-AP-joran-van-der-sloot-100604119865.png.rend.hgtvcom.231.174.suffix/1698172052978.png)

![Rebekah Gould [main] was murdered in 2004. In 2022, William Miller [inset] was sentenced for her murder.](http://investigationdiscovery.sndimg.com/content/dam/images/investigationdiscovery/crimefeed/legacy/2022/10/larry-gould-rebekah-gould-izard-county-sheriffs-office-william-alama-miller-10252022.png.rend.hgtvcom.231.174.suffix/1666723970508.png)