How Are The Wrongfully Convicted Compensated For Lost Years Of Their Lives?

The law guarantees individuals exonerated of federal crimes $50,000 for every year spent in prison and $100,000 for every year spent on Death Row.

![West Memphis Three: Damien Echols, Jessie Misskelley, and Jason Baldwin [Wikimedia Commons]](http://investigationdiscovery.sndimg.com/content/dam/images/investigationdiscovery/crimefeed/legacy/2018/10/West_Memphis_Three_Mugshot_10022018.jpg.rend.hgtvcom.616.347.suffix/1538599964275.jpeg)

West Memphis Three: Damien Echols, Jessie Misskelley, and Jason Baldwin [Wikimedia Commons]

How much is each year of your life worth? For an inmate who was wrongfully convicted and then exonerated, sadly the answer is that it depends on where they were convicted.

People who are wrongfully convicted and later exonerated through DNA evidence spend an average of more than 14 years behind bars, according to The Innocence Project. But once they gain freedom, many former inmates find that their nightmare is just beginning.

They very often have no money, housing, transportation, health services, or insurance — and they may still have a criminal record, which makes it more difficult to get all of those things.

According to the National Registry of Exonerations, 2,000 wrongfully convicted individuals have been exonerated for state and federal crimes since 1989.

In 2016, there were 166 exonerations nationwide — an average of more than three per week.

In 2004, Congress passed the Justice for All Act with bipartisan support. The law guarantees individuals exonerated of federal crimes $50,000 for every year spent in prison and $100,000 for every year spent on Death Row.

But at the state level, experts say, compensation varies widely. Thirty-three states have compensation statutes of some form, while some states — including Arizona, Arkansas, and Wyoming — have none at all.

Texas, a state known for being tough on crime, has one of the most comprehensive statutes on the book. The wrongfully exonerated are paid $80,000 for every year spent in prison and are eligible for monthly annuity payments after release. Over the years, the state has paid over $93 million to wrongfully convicted individuals, according to The Pew Charitable Trusts.

But the law cannot help prisoners who are released without being officially exonerated — like Ed Ates, who spent 20 years incarcerated in Texas after being convicted of the 1993 murder of Elnora Griffin. Ates' case was covered on season two of the Truth & Justice podcast and the Innocence Project of Texas.

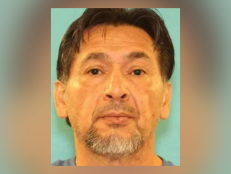

![Edward Ates [Texas Dept. Of Criminal Justice]](http://investigationdiscovery.sndimg.com/content/dam/images/investigationdiscovery/crimefeed/legacy/2018/10/edward-ates-10022018.jpg.rend.hgtvcom.616.493.suffix/1538599950881.jpeg)

Edward Ates [Texas Dept. Of Criminal Justice]

He was paroled earlier this year, and his lawyers have said that they are filing motions to re-test old DNA evidence in an attempt to officially exonerate him.

Wisconsin's compensation is a mere $5,000 for every year spent in prison. The compensation is capped at a maximum of $25,000, no matter how long the former inmate has spent behind bars.

Iowa's statute provides up to $50 per day of wrongful incarceration plus lost wages up to $25,000 a year, plus attorney's fees.

Some states offer other benefits: Vermont, for example, provides health-care coverage for 10 years after an exonerated individual is released from prison.

In states without any compensation laws, people who are exonerated have to file a lawsuit to get compensation. The process can be long and expensive — and there is no guarantee of winning.

Historically, most of the cases that resulted in exonerations have been high-profile murder cases. But in recent years, an increasing number of lower-level offenses, including drug convictions, have been overturned.

A steady increase in exonerations in recent years, often a result of new DNA-testing capability, has prompted lawmakers in many states to increase the amount of compensation available to the wrongfully convicted and to make the process easier.

In Kansas, legislators have introduced a bill that would give individuals who were wrongfully convicted up to $80,000 for each year they spent behind bars. The bill would help residents like Floyd Bledsoe, who was 23 in 2000 when he was sentenced to life in prison plus 16 years for the murder of his 14-year-old sister-in-law, Zetta “Camille” Arfmann.

Bledsoe was vindicated in 2015 after his brother Tom Bledsoe confessed to the murder in a suicide note before taking his own life. Within a month, his conviction was vacated. But after leaving prison, he had nothing. “Before I was locked up, I had 40 acres, livestock, a wife and kids,” he told The Pew Charitable Trusts. “When I was released, I had nothing … I lost my family, my job, my reputation — everything.”

In nearby Michigan, Republican Governor Rick Snyder signed a bill that pays $50,000 for each year of wrongful imprisonment and provides services to assist in re-entering the community after release.

As the debate continues on the state level, another sticking point is what counts as "exoneration": Some politicians believe that to be eligible for compensation, a wrongfully convicted person would have to be exonerated through DNA evidence, while others believe that a judge vacating the conviction should be enough.

What about individuals who pleaded guilty or no contest to a crime?

New legislation in these areas could affect cases like the West Memphis Three — Damien Echols, Jason Baldwin, and Jessie Misskelley — who were in prison for almost 18 years for a murder of three young boys.

They were released after accepting an Alford plea, which allows defendants to assert their innocence, while conceding that the state has enough evidence to convict them. But even in a "best case" scenario — with high-profile celebrities including Eddie Vedder and Johnny Depp on his side, a happy marriage, and a very public release from Death Row — Echols told The Guardian that his struggle continued following his release.

“People think if you see someone on TV, talking to celebrities, they must be wealthy, doing okay,” Echols said. “But nothing could’ve been further from the truth. When I got out, I couldn’t read, I couldn’t watch TV, I couldn’t do my daily magick routine. It shattered me psychologically.”

The Arkansas Supreme Court has unanimously ruled that the West Memphis Three were entitled to hearings on whether they could use the state's DNA exoneration statute for post-conviction DNA testing.

Read more: The Innocence Project , Pewtrusts, Time, Texas Monthly

![Michael Peterson [left] and Kathleen Peterson [right] smile. He is wearing sunglasses, a white shirt, and a hat and she is wearing a black shirt.](http://investigationdiscovery.sndimg.com/content/dam/images/investigationdiscovery/crimefeed/legacy/2022/04/an-american-murder-mystery-the-staircase-S1-E1.png.rend.hgtvcom.231.174.suffix/1651263591477.png)

![Steven Stayner as he testifies about his abduction in 1972 by Kenneth Eugene Parnell and his seven years in captivity [left]; Cary Stayner's mug shot after being arrested in connection with the murder of four women [right].](http://investigationdiscovery.sndimg.com/content/dam/images/investigationdiscovery/crimefeed/legacy/2022/04/AP-steven-stayner-770000199398-FBI-cary-stayner.png.rend.hgtvcom.231.174.suffix/1651011166523.png)